Sesquicentennial

History, part 4

No Longer

a Frontier Church, 1873-1921

The changes overtaking First

Congregational Church in the years following the Civil War were

many. Some of these changes occurred within the congregation

itself. In 1873 Luther Clapp resigned to become General

Missionary of the Milwaukee Congregational Convention, a position

in which he aided a number of weaker churches in the region. He

left a strong church but one that would not again experience a

pastorate of a decade or more until the twentieth century (see

Appendix for List of Ministers). All the while, the community

around the Church was growing, and changing. By the 1870s

Wisconsin was no longer the frontier and Wauwatosa ceased to be a

farming community and more and more assumed its current role as a

suburb of Milwaukee.

Growth in Wauwatosa meant

growth in the congregation of the Church that required

accommodation. In 1870 a lecture hall had been added to the rear

(west) of the Church.

Built at a cost of $2,076.29, it was

entered through doors on either side of the front of the

sanctuary. Additional growth led to further expansion of the

Church's physical plant. A parsonage was constructed for $2,200

in 1884 opposite the Church. In 1888, at a cost of about $8,000,

the original Church building was raised and a "good

basement" constructed. A vestibule was added to the front

(east side) of the church, red-cushioned

Built at a cost of $2,076.29, it was

entered through doors on either side of the front of the

sanctuary. Additional growth led to further expansion of the

Church's physical plant. A parsonage was constructed for $2,200

in 1884 opposite the Church. In 1888, at a cost of about $8,000,

the original Church building was raised and a "good

basement" constructed. A vestibule was added to the front

(east side) of the church, red-cushioned

theatre seats replaced

the original pews, and a space was provided for the eventual

placement of an organ behind the pulpit.

theatre seats replaced

the original pews, and a space was provided for the eventual

placement of an organ behind the pulpit.

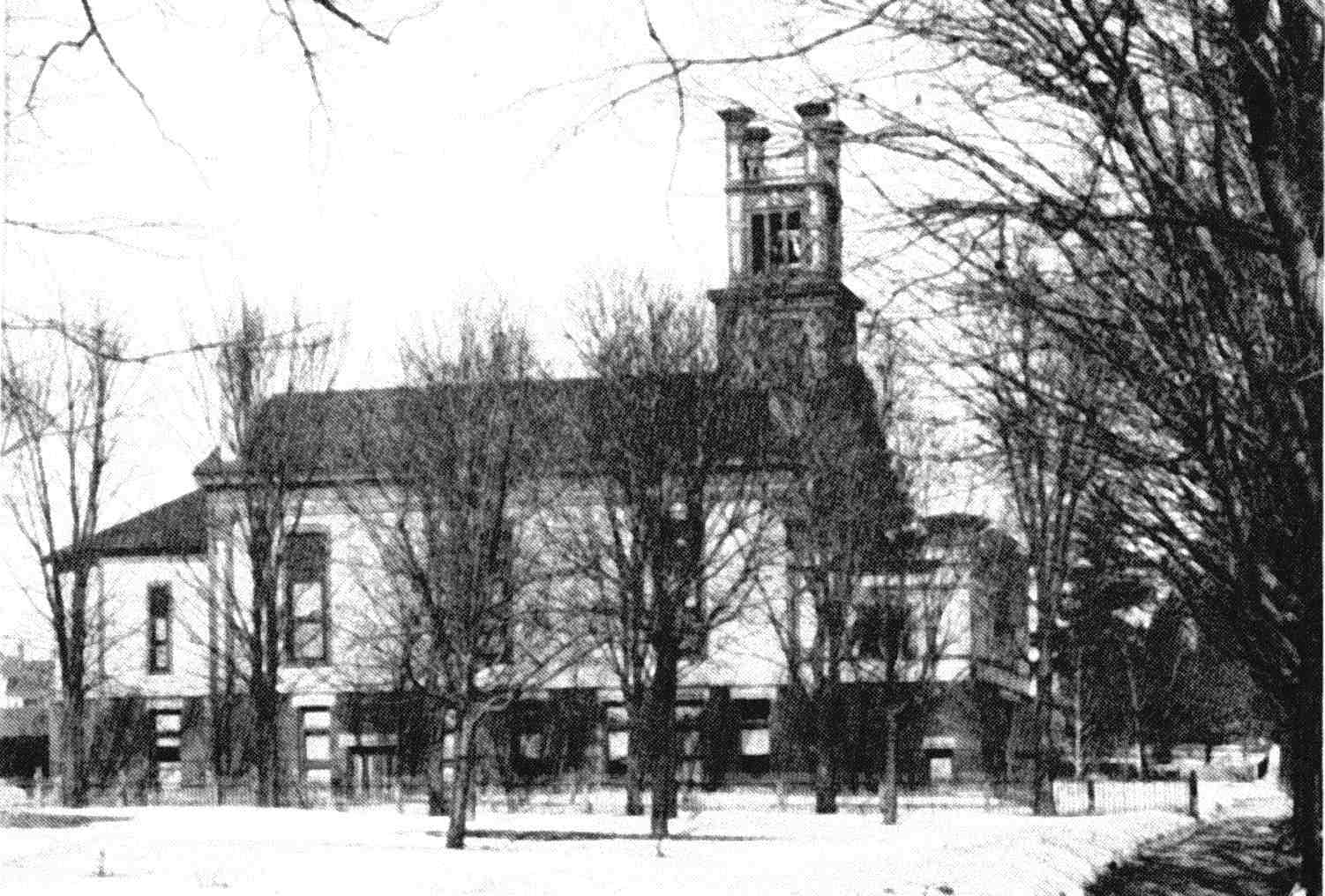

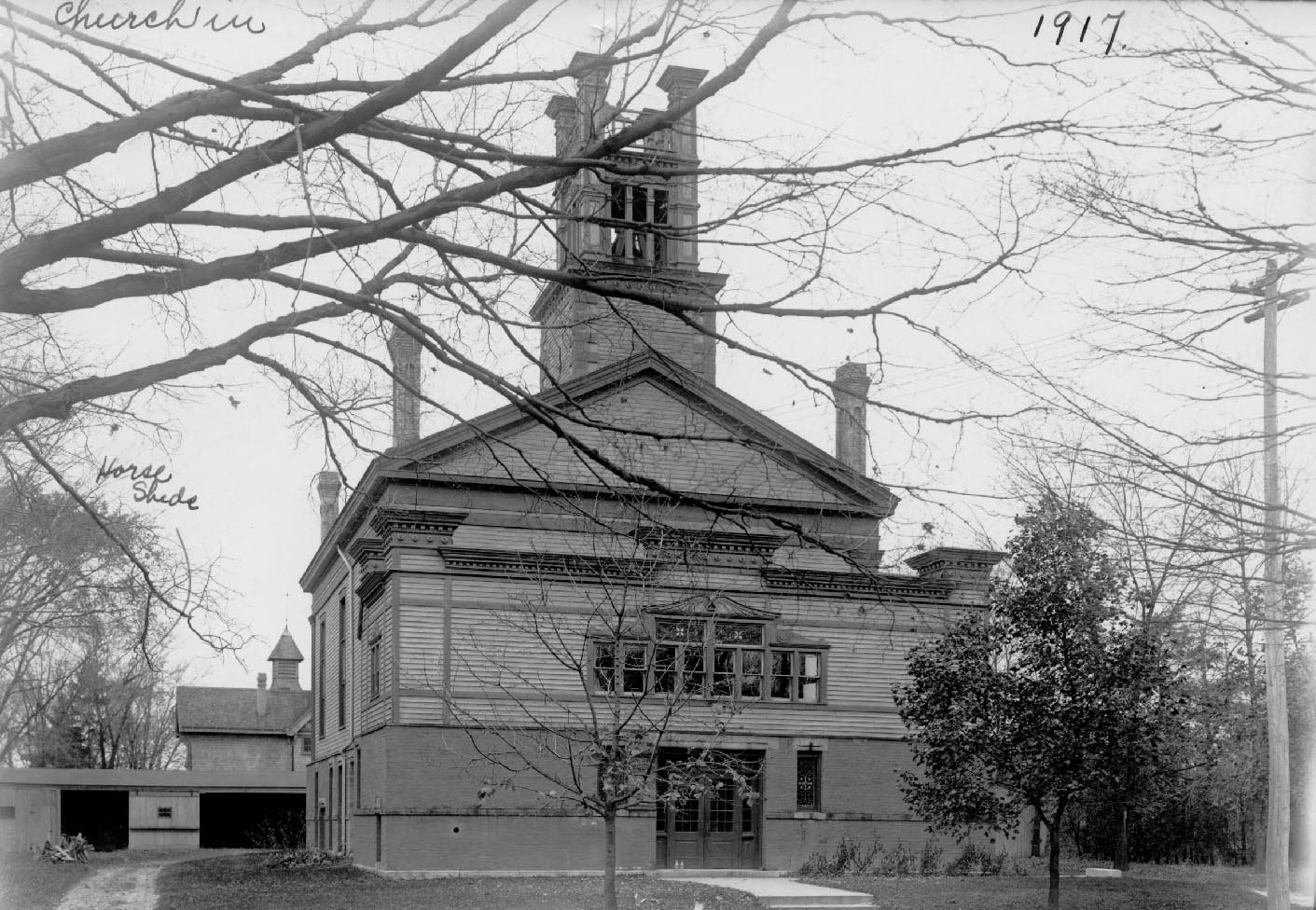

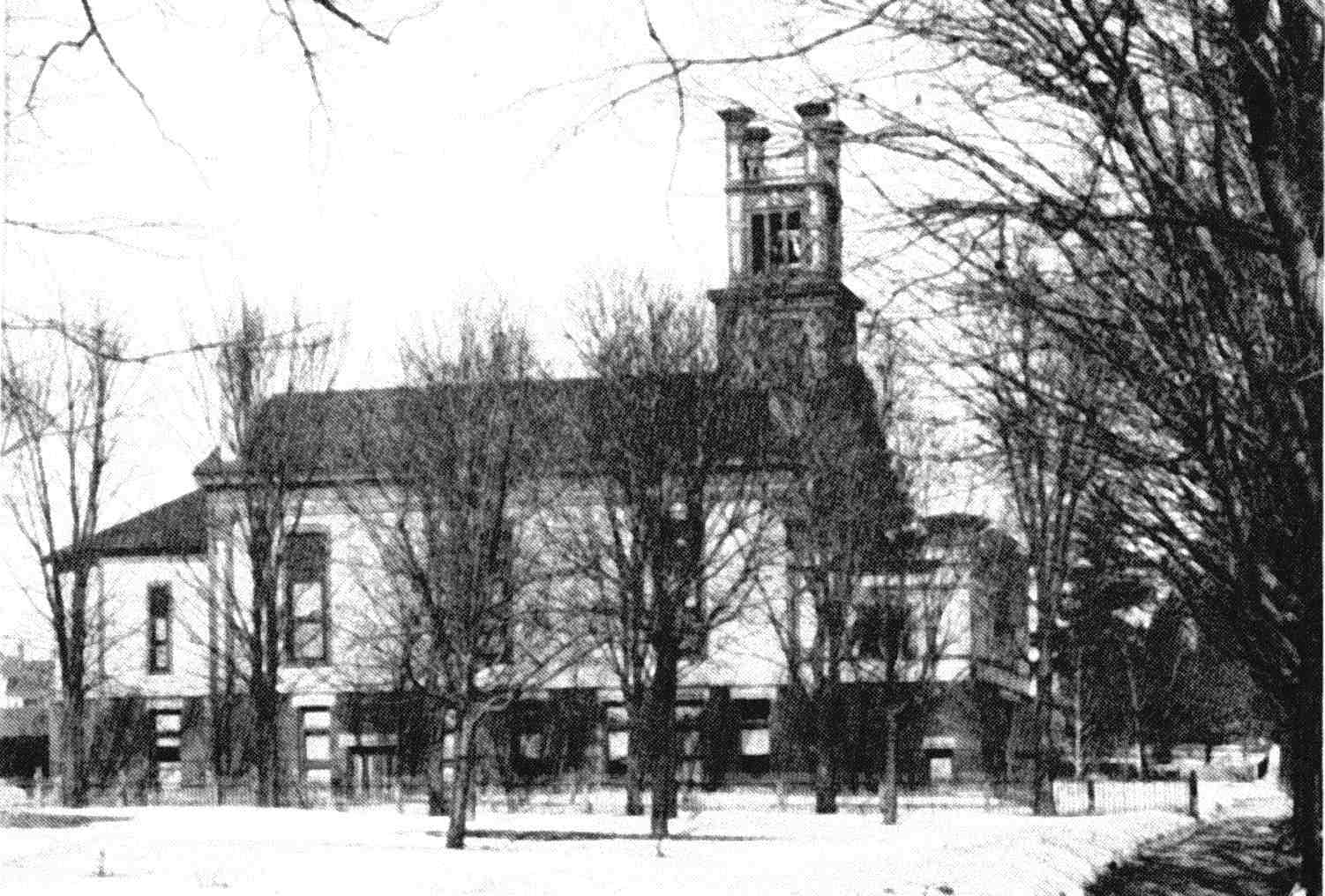

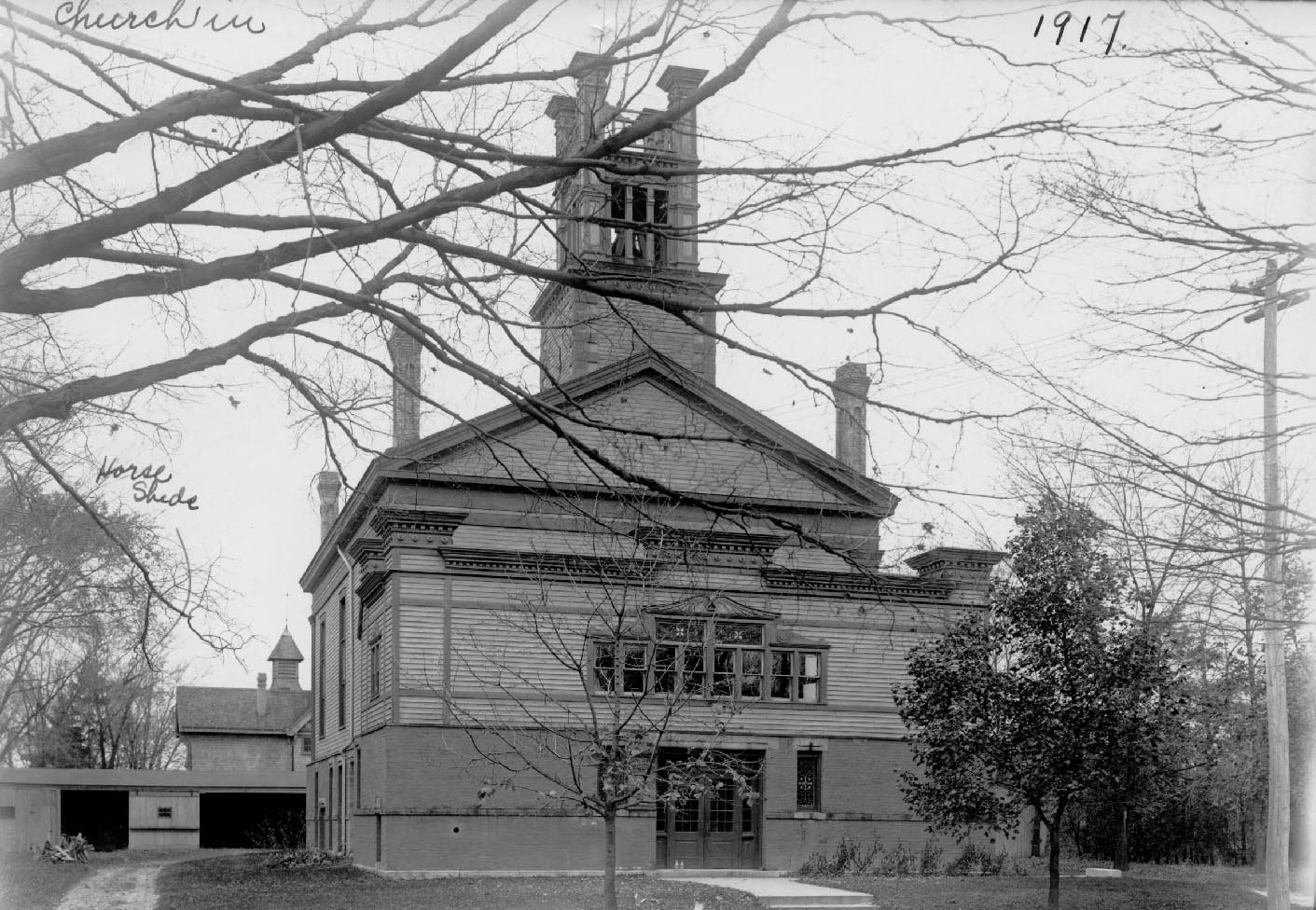

(NOTE: Three views of the 1888 church: side, front, and the Nave internals with the Organ

installed)

Such renovation

of the original

building, however, still failed to meet the needs of a growing

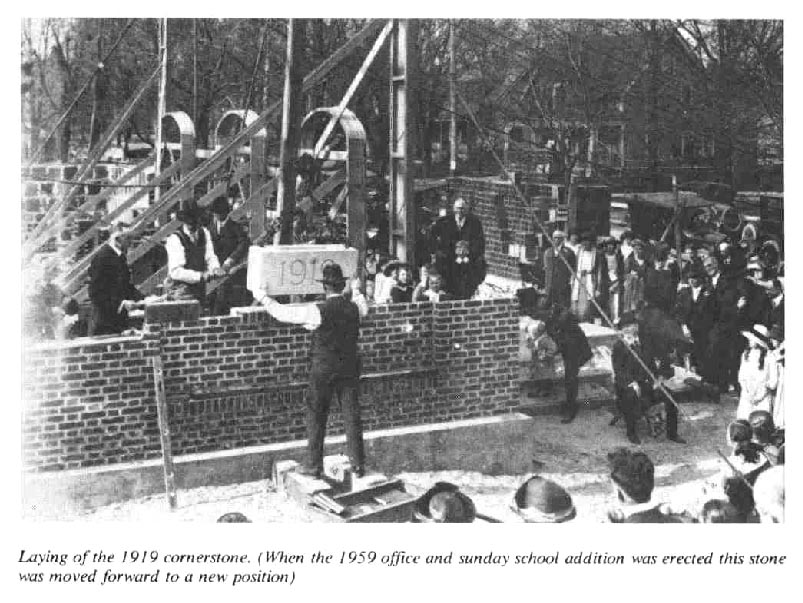

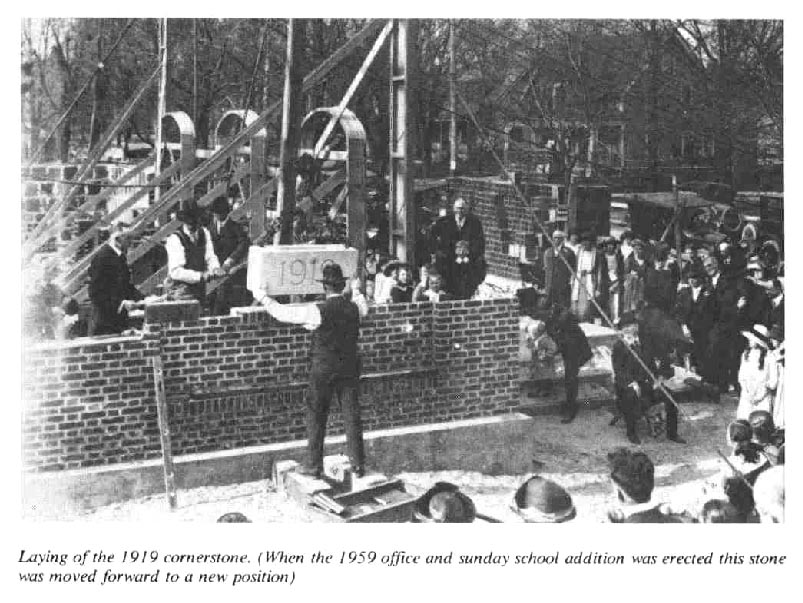

congregation. At the annual meeting in 1911 a sinking fund was

established for a new building, and the Church's seventy-fifth

anniversary, although observed on the brink of World War I on

March 1, 1917, provided the opportunity to accelerate fund

raising for a new church. With the end of World War I,

construction became possible. The last services were held in the

original Church on July 20, 1919 because the new Church was to be

built on the site of that structure. For several months, the

congregation was without a home: it held joint services with the

Methodists, who also were building a church, in the

of the original

building, however, still failed to meet the needs of a growing

congregation. At the annual meeting in 1911 a sinking fund was

established for a new building, and the Church's seventy-fifth

anniversary, although observed on the brink of World War I on

March 1, 1917, provided the opportunity to accelerate fund

raising for a new church. With the end of World War I,

construction became possible. The last services were held in the

original Church on July 20, 1919 because the new Church was to be

built on the site of that structure. For several months, the

congregation was without a home: it held joint services with the

Methodists, who also were building a church, in the

Masonic

Temple through August 17, 1919; and then the congregation held

Sunday afternoon services in the basement of Underwood Baptist

Church.

Masonic

Temple through August 17, 1919; and then the congregation held

Sunday afternoon services in the basement of Underwood Baptist

Church.

Finally, the Congregation

leased the lot on the southeastern corner of Church Street and

Milwaukee Ave. and there constructed, with donated materials and

the congregation's labor, led by the example of its minister

Howell Davies, a structure known as "The Tabernacle"

that was used for services from November 1919 through May 1921.

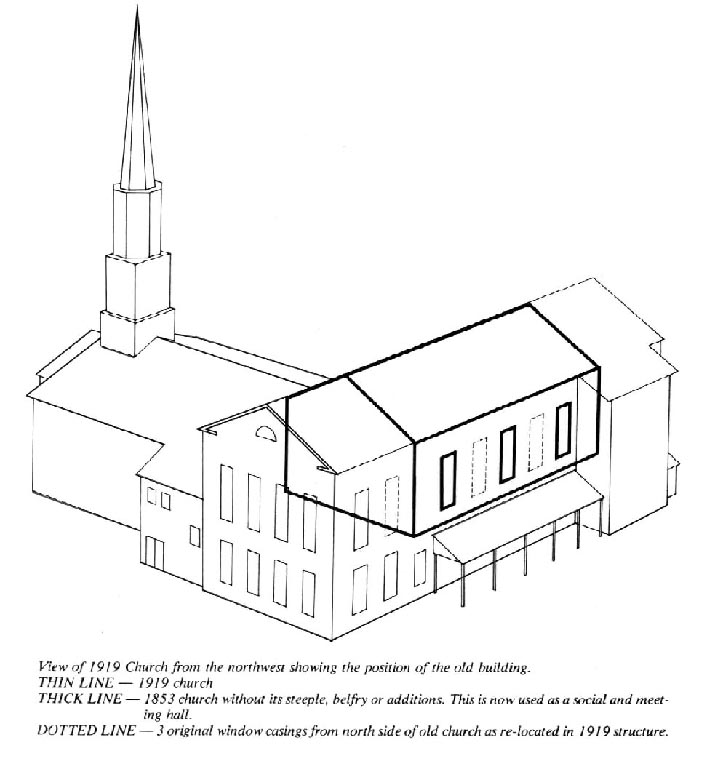

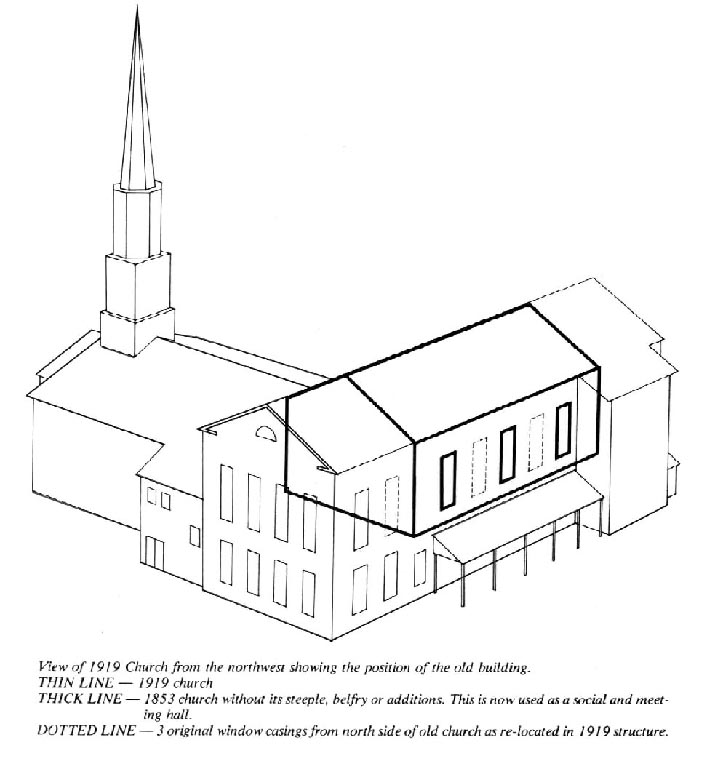

On May 20-23, 1921 the Church

dedicated its new sanctuary. Designed by architect E.E. Kuenzli,

a Church member, the building and its furnishings represented an

investment of $118,258.04 funded in part by a mortgage of

$38,650.00 on the Church and parsonage. This sanctuary, presently

still in use,

was connected to the original structure which had

been turned ninety degrees

was connected to the original structure which had

been turned ninety degrees

and moved back on the Church grounds

to form a wing for Sunday School classrooms and recreation

facilities.

and moved back on the Church grounds

to form a wing for Sunday School classrooms and recreation

facilities.

The activities of the

congregation in the late nineteenth and early twentieth

centuries

were numerous because this church, like so many others of the

period was really the center of its members' social as well as

religious lives. Church benevolence grew in size and scope of

interest, and by its fiftieth anniversary the Church had

contributed $23,526.97 to such worthy causes as Beloit College

($13,100), Chicago Theological Seminary ($900), Ripon College

($200) and missions ($9,326.97).

centuries

were numerous because this church, like so many others of the

period was really the center of its members' social as well as

religious lives. Church benevolence grew in size and scope of

interest, and by its fiftieth anniversary the Church had

contributed $23,526.97 to such worthy causes as Beloit College

($13,100), Chicago Theological Seminary ($900), Ripon College

($200) and missions ($9,326.97).

The various nineteenth-century

women's groups merged into the Women's League in 1907 and that

body first divided into circles in 1921. Women also participated

in the Daughters of the Tabernacle, a group meeting in the

evenings that drew its name from the Church's temporary place of

worship, and the World Fellowship Council interested particularly

in missionary work. Indeed, interest in missions was great and

several women of the Church went into missionary work, including

Sarah Clapp Goodrich who worked in China. Women's groups,

particularly the League, did much other important work for the

Church, financing Weekday Bible School with their fund raising,

running the Junior Choir and the Nursery, staffing a Hospitality

Committee to contact potential new members and visit shut-ins,

and providing meals for important Church events.

Youth activities assumed

increasing importance in the life of the Church in this period.

The focus of youth activities in the late nineteenth century and

the first years of the present century was the Young People's

Society for Christian Endeavor, an international,

interdenominational Christian Youth group founded in 1881. It was

supplanted in First Congregational Church in 1925 by the Pilgrim

Fellowship. Ministry to the youth of the community was further

enriched by the opening of Weekday Bible School in 1923. In this

endeavor, the Church was something of a leader. After his arrival

in 1925, the Reverend Henry James Lee prepared lessons for this

program which were used for a time by the majority of Milwaukee

area churches conducting such programs. Today, in 1992, First

Congregational Church's weekday program remains as one of the few

such programs in the metropolitan area.

As the First Congregational

Church changed, so did much around it. America became an

urbanized society in the early twentieth century, and the

automobile, as a former Church member from the era, Thomas

Kraseman, recalled, brought a personal mobility that spelled the

end of the Church's primacy in social life. Congregationalism

itself was also changing in very significant ways.

Developments in American

Congregationalism in the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries

certainly reflected developments in American Protestantism as a

whole. There was a growing desire among many for Christian unity

and for centralization of denominational activities. Many would

find in such trends increasingly disturbing contradictions of the

Congregational Way.

American Congregationalists

founded the National Council of Congregational Churches (NCCC) at

an Oberlin, Ohio meeting in 1871. Delegates representing 3,300

congregations concurred that the NCCC was not established to

abridge "the scriptural and unalienable right of each church

to self-government and administration," but they went on to

state their desire "to cooperate with all the Churches of

our Lord Jesus Christ . . . It is our prayer and endeavor that

the unity of the Church may be more and more apparent, and that

the prayer of the Lord for his disciples may be speedily and

completely answered, and all be one . . ."

The Oberlin actions provided

the basis for increasing efforts at both centralization of

Congregational activities through the NCCC and a federation with

other Protestant groups. The NCCC in 1910 created a Commission of

Nineteen to coordinate and develop national budgets for

Congregational benevolence and in 1913 appointed a full-time,

paid General Secretary. Christian unity efforts continued at the

same time. In 1892 Congregational Methodist Churches in Alabama

and Georgia affiliated with the NCCC and in 1931 the NCCC joined

with the General Convention of Christian Churches to form the

General Council of Congregational Christian churches.

The almost five decades

encompassed in this period of our history culminated, therefore,

with a stronger First Congregational Church. Housed in a new

building and part of an increasingly urbanized America, the

Church, however, found itself also part of a religious fellowship

in which there was apparent tension between the traditional

independence of individual churches and the growing institutional

structure of denominational governance.

Next Page: The Challenges of the 20th Century

1921-1991

Back to History Page:

A

Sesquicentennial History

Built at a cost of $2,076.29, it was

entered through doors on either side of the front of the

sanctuary. Additional growth led to further expansion of the

Church's physical plant. A parsonage was constructed for $2,200

in 1884 opposite the Church. In 1888, at a cost of about $8,000,

the original Church building was raised and a "good

basement" constructed. A vestibule was added to the front

(east side) of the church, red-cushioned

Built at a cost of $2,076.29, it was

entered through doors on either side of the front of the

sanctuary. Additional growth led to further expansion of the

Church's physical plant. A parsonage was constructed for $2,200

in 1884 opposite the Church. In 1888, at a cost of about $8,000,

the original Church building was raised and a "good

basement" constructed. A vestibule was added to the front

(east side) of the church, red-cushioned

theatre seats replaced

the original pews, and a space was provided for the eventual

placement of an organ behind the pulpit.

theatre seats replaced

the original pews, and a space was provided for the eventual

placement of an organ behind the pulpit.